Feminist Futures Fellows: Kayleigh Perkov

We're proud to share with you the work of our 2019-2020 cohort, the Feminist Collaboratory Fellows. The year's research theme is Feminist Futures, and through the Collaboratory we provide resources to independent scholars who are pursuing feminist thought and practice in their research. We asked each fellow to participate in a video or written project to display their work and explore the theme further. This is the second installment of that series.

Introduction

Introduction

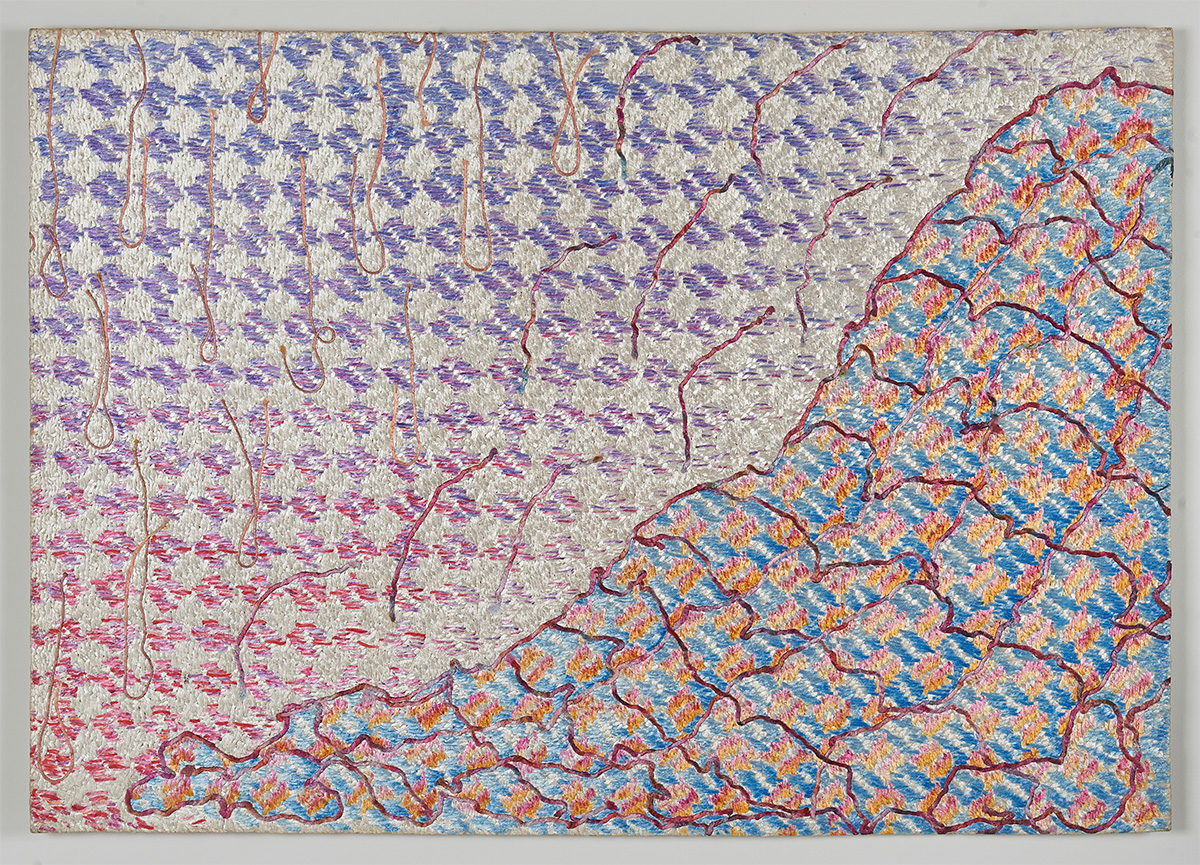

My name is Kayleigh Perkov. I am a scholar who looks at craft and, in particular, the intersection of traditional forms of handmaking,emergent technology, and gender. The project I was working on at FRI is titled The Computer Repays Its Debt: Women Technology And Textiles From 1965 To 1985. This is an exhibition currently up at the Center of Craft in Asheville, North Carolina, which looks at a series of makers who integrated textiles and technology.

What planted your first seeds of interest in this research subject?

I was researching some exhibitions from the mid ‘60s, and I came across a woman by the name of Janice Lourie. She was an IBM computer programmer. Lourie was hired in the late ‘50s, which is actually a historic period in which companies like IBM were recruiting quite a number of women. She was also an amateur weaver from a young age. After working on some of the very first computer-aided design (CAD) programs at IBM, she got enough leeway to start her own independent research project. The project she chose was the development of CAD software for mechanized weaving. IBM actually utilized Lourie and her software in a number of public relations campaigns.

I really got interested in how, in the late 1960s, this weaving software was harnessed to make computers seem more humane and approachable at a time when many Americans were becoming suspicious of large technological corporations. I discovered a really great quote from a software manager at General Electric who said something to the effect of: "If we can't convince people that computers are for them, people won't be for computers." So I got really interested in how these forms of feminized making were used to make computers seem more appealing and less intimidating.

Do you have a personal connection to crafting?

Yes, I do. I'm a first generation college student, and my family, despite living in Los Angeles, wasn't a family who went to art museums. I didn't go to many art shows until I declared myself an art history major as an undergraduate. But what my family did was craft. So my grandma would crochet, and she would embroider. From a young age, I would embroider and crochet with her, and these are the forms of art that were around as I was growing up. So when it came for time for me to specialize in my academic studies, I was organically drawn to these ways of making, and questioning our assumptions and hierarchies of the visual arts.

What would a feminist future look like, and how does your work contribute to its realization?

This actually touches on the title of my project, The Computer Pays Its Debt. I find that a lot of projects that think about what a more equitable world of technology would be like generally focus on issues of gender parity and recruitment. The idea is that if we get more women into STEM and technology, we will achieve a more equitable world. While I think recruitment is a laudable goal, I question the idea that it is sufficient.

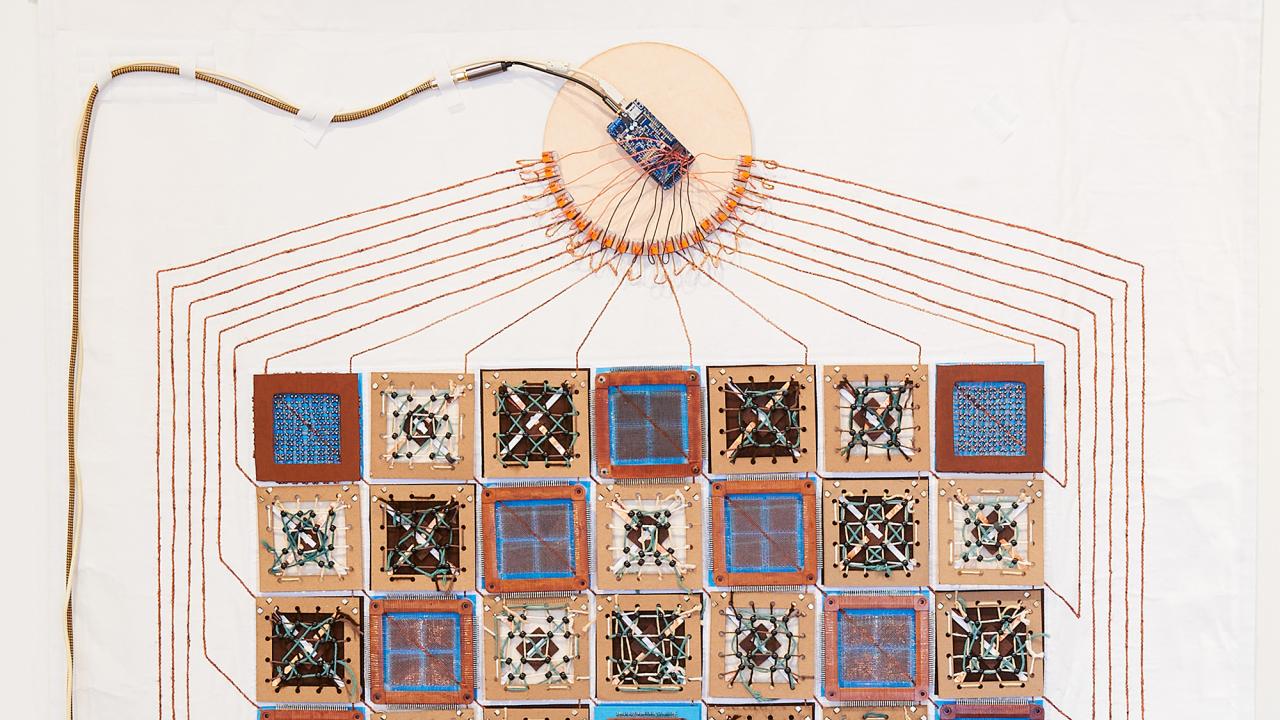

Women undergird the history of computing, not just writing software as in ENIAC (the first electronic computer), but actually the manufacturing of computers and computer memory. For example, one of the people I talk about in my exhibition is a woman by the name of Hilda Carpenter who hand-wove some of the first core memory planes for the Whirlwind computer. This is another situation of feminized labor and weaving coming together in the history of computers. Carpenter was a woman of color. There's quite a lot of work from women of color who created the hardware of computing that has gone unacknowledged in the history of the field, by and large.

So this idea that simply adding women into computing is going to create a more equitable world, I think, should be viewed with a lot of suspicion. My work is really trying to think about how feminized labor has functioned within computing, and what it would take to create a more equitable future more broadly, and what type of works would need to be acknowledged and valued for that to happen.

How might your expertise help us think about the ongoing pandemic?

One of the things I've been thinking about, and I don't think I'm alone in this in the craft community, is the ways in which many at-home makers stepped up to the shortage of PPE, in particular, with regards to sewing masks and sharing diagrams and knowledge and how-to and distributing these things. I don't in any way want to diminish what I'm sure was a very powerful gesture in using one's knowledge to better public health. I think it’s a very powerful thing to share. But I also want people to be thoughtful in how this labor is gendered, even if it's undertaken by people who don't identify as women, and is therefore undervalued and viewed as something that is just a labor of love, and not worth giving any sort of monetary value to. I think that sort of handmaking craft labor segues into how we think more largely about care-based labor and what type of work we value, what type of work we don't value, and how we show our value.

Reflecting on this moment, what would you like to see change?

One of the things I've been thinking about is how we assign value to work. I know a lot of folks have been chafing at how we call certain forms of work essential but don't allow those workers to make a living wage or get access to adequate protections and care. And again, that doesn’t always fall along traditional gender hierarchies, gender norms or views of gendered work, but it often does.

Another area of my work that I've been thinking about a lot is the development of wearable biosensors, self-tracking, and issues of surveillance. I’ve been studyinga jeweler from the 1970s named Mary Ann Scherr who created some of the very first wearable biosensors, and part of my work on her is just how quickly those devices were harnessed for larger public health surveillance. The EPA approached her in the late ‘70s. So I've been thinking a lot about the trade-offs between greater knowledge of one's environment and one's body versus the loss of privacy and the act of participatory surveillance.

What would you like people to take away from your work?

I think one of the things I have always tried to make people take away from my work is that, even though we tend not to acknowledge it, we still live in a world where there's a lot of hand labor. We should be really attentive to the forms of hand labor that are around us and what types of labor we acknowledge and valorize. For example, right now everyone's stuck at home baking sourdough. This is a hand labor that's lauded and loved and celebrated. But there's other hand labor that's incredibly valuable, which really drives our daily life, and we might call it essential but we don't really value it. So just really being attentive to hand labor is something I always strive to get people to think about.

For more information about Kayleigh’s work:

The Computer Pays Its Debt: Women, Textiles, and Technology, 1965-1985