Working Toward Mobility Justice

“If we want to explain the injustices around transportation in the United States today, there’s an answer,” Mimi Sheller said as part of a two-day workshop on mobility justice organized by the Feminist Research Institute (FRI) at UC Davis. “The inequalities of our transportation system are based in white supremacist, heteromasculine, patriarchal racial capitalism, built upon Indigenous land theft and attempted genocide.”

Sheller, who is Professor of Sociology and Director of the Center for Mobilities Research and Policy at Drexel University, delivered her keynote speech on November 1. After Sheller’s talk, participants from diverse disciplines and institutions gathered to co-create research agendas inspired by a commitment to mobility justice. The workshop, titled Addressing Cycles of Inequality, was supported by the FRI in partnership with the National Center for Sustainable Transportation and the Institute for Transportation Studies.

Mobility justice, according to Sheller, is “an overarching concept for thinking about how power and inequality inform the governance and control of all forms of movement.” This umbrella term “can help us connect personal embodied experiences of injustice with neighborhood scale, national scale, and global scale injustice,” Sheller said. On each of these levels, Sheller argued, the capacity to self-determine one’s movements is dependent on intersecting systems of oppression like racism, sexism, classism, and ableism. Mobility justice helps us understand, for example, how the experience of someone who is forced to constantly move because of homelessness is related to the experiences of migrant workers or climate refugees.

Sheller argued that “white power is built upon the construction and empowerment of a specifically mobile white, heteromasculine, national subject.” Because the liberal subject is a moving subject, she said, to police mobility is to police who can be free. Political action requires the right to assembly, but access to a car, the ability to safely ride a bike, or the use of public transportation are all impacted by systems of power and inequality.

At the conclusion of her talk, Sheller asked: “What do we do in the face of mobility regimes?” She suggested several routes for action and thought rooted in Black feminist theory and the Black radical tradition, including Katherine McKittrick’s work on Black women’s geographies, which offers “a different way of imagining movement.” She cited the work of The Untokening, a mobility justice collective that, according to its website, "centers the lived experiences of marginalized communities to address mobility justice and equity."

Sheller also described a bike party she experienced in New Orleans, where a group of people slowly cycled by, blasting music, and festooned in lights. Examples like this, Sheller said, are underrepresented in bike policy and transportation equity discussions, and suggest a way of being in the streets that can build community and healing for Black, brown, and Indigenous people of color.

In the following day’s workshop, an interdisciplinary group of invited participants worked to create a collaborative research agenda centering mobility justice that reaches across traditional disciplinary divides. Scholars from a wide range of fields including sociology, psychology, transportation studies, engineering, human services, anthropology, history, urban planning, communications, policy, and cultural studies responded to the questions: “What visions do you have for the future of mobility justice research? How would you like the types of questions we ask and how we answer them to change? What challenges might keep us from reaching that vision?” They participated in vision mapping exercises and shared the results of those exercises with one another, collaborating on a mobility justice research agenda to inform future work in their home institutions and disciplines.

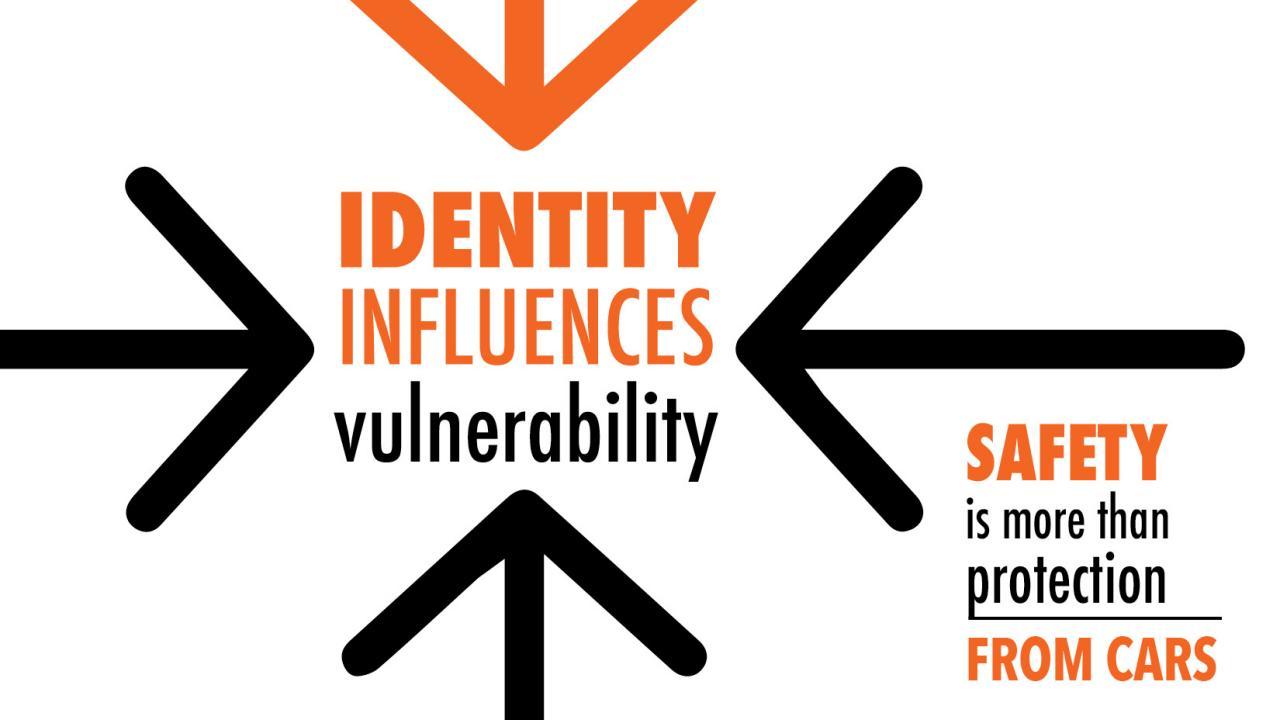

Sarah McCullough, Associate Director of the Feminist Research Institute, described some of the thinking that came out of this workshop: “We discussed how we can use our research expertise to positively impact communities, influence decision makers, and create more accountability for histories of inequality and ongoing structures of oppression. For example, studying street safety must mean more than just studying car crashes. From a mobility justice perspective, street safety also means examining over-policing in communities of color, street harassment faced by women, trans, and gender-nonconforming individuals, and other forms of more subtle violence such as housing displacement and traffic pollution. When calling for safer streets, we must always ask, safer for who? Going forward, we plan to continue the conversation in regular convenings with the goal of producing research statements, curriculum, and new projects.”